Asia Profiles: Japan

Overview

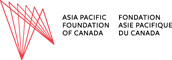

Download as PDFJapan is an archipelago of four main islands and nearly 4,000 smaller islands. Its islands stretch north toward Russia and south toward Taiwan, covering a span of roughly 2,400 kilometers. Japan has a rugged landscape, with mountains covering 80 percent of its land surface. The highest peak, at 3,776 meters, is the famous cone-shaped Mount Fuji. Japan is also in a danger zone for earthquakes, with about 1,000 per year, as well as 60 active volcanoes.

Map 1: Japan.

Map 1: Japan.

Basic Facts

- Population: 126,451,398 (percentage under 25 years: 22.48%)

- Life Expectancy: 85 years

- Literacy Rate (age 15 and over can read & write): 99%

- Official and Major Language(s): Japanese

- Type of Government: Parliamentary constitutional monarchy

- Current Leader: Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

Internet and Social Media

- Active Internet Users: 93% of population

- Average Daily Internet Use: 4.2 hours

- Active Social Media Users: 42% of population

- Average Daily Social Media Use: 0.80 hours

Economy

- GDP: C$6,327.45 billion

- GDP per capita: C$49,921.45

- Currency: Japanese Yen

Exports: motor vehicles, iron and steel products, semiconductors, auto parts, power generating machinery, plastic materials

Imports: petroleum, liquid natural gas, clothing, semiconductors, coal, audio and visual apparatus

Aging Japan in the Age of Robots

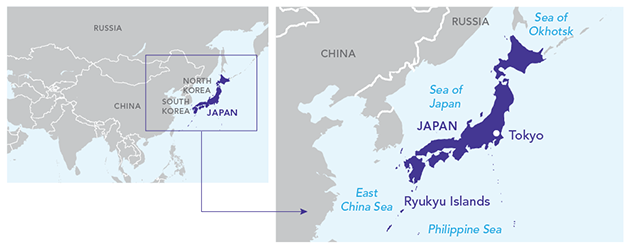

Figure 1: Population Pyramids (in millions)

Figure 1: Population Pyramids (in millions)

Japan’s population is one of the oldest in the world, with more than one quarter of its people over the age of 65. This is due to two main factors: its long life expectancy, which is 85 years old, and its low birthrate, which is only 1.5 babies per woman. (A population needs a birth rate of 2.1 live births per woman to ‘replace’ itself from one generation to the next.) As a result, Japan is having to prepare for a shortage of working-age people, especially people who can provide assistance to the growing number of elderly people. To illustrate the size of this gap, it is estimated that by the year 2025 Japan will face a shortage of 370,000 nurses.

That’s where robots come in.

Figure 2: Video: "Can Robots Take Care of the Elderly?"

For many decades, Japan has been a leader in developing new technologies. Now, it is using its technological skills to design robots that will fill the growing gap in care workers. What are these robots able to do? One robot called Robear can lift people from their wheelchairs or beds. Not only is Robear stronger than a human being, but it also doesn’t suffer from a sore back or other injuries caused by lifting heavy objects. A robot called Pepper serves a different function—‘she’ can entertain and interact with people by singing, dancing, and having simple conversations. Unlike humans, Pepper can be available any time of the day, and doesn’t get tired. That’s not always the case with human caregivers. Similarly, robotic pets can help alleviate loneliness, an issue that affects many elderly people. For example, a robotic seal called Paro can blink and respond to people’s touch. Robotic dogs can bark and sit like real dogs, but don’t require baths and daily walks, and don’t make a mess on the carpet.

How do Japanese people feel about robots in their daily lives? According to one survey, 65 percent of Japanese people say they are willing to be taken care of by “nursing robots.” Another survey shows that elderly Japanese feel that humanoid (human-like) robots will play a positive role in their daily lives. Some people in Japan claim that robots can have unique personalities, and even a ‘soul.’

Figure 3: Video: "The Soft Side of Robots: Elderly Care"

Japan is not the only country thinking about how to adapt to an increasingly aging population. Canada, China, and most countries in Western Europe are following close behind, with longer life expectancies and birth rates below the replacement rate. Therefore, Japan’s experience with robots could contain lessons for people in other parts of the world. This includes asking questions about this experience, such as, What are the benefits to incorporating robots in our daily lives? Are there any dangers? Should robots be a part of everyone’s daily life, regardless of age? Can they be better companions than humans? And Should robots also replace other types of workers, such as teachers, police officers, bus drivers, and politicians?

The Geography of Japan's Natural Disasters

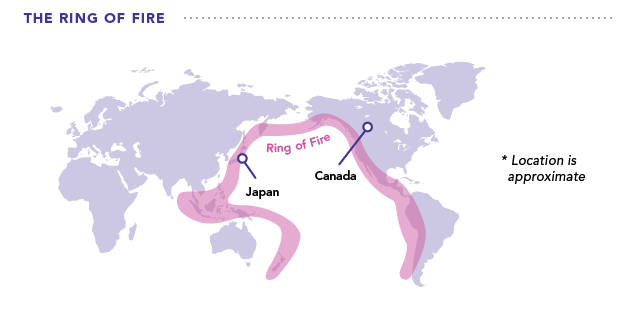

Figure 4: The Ring of Fire

Figure 4: The Ring of Fire

Japan’s geography makes it very susceptible to natural hazards. It sits along the ‘Ring of Fire,’ a horseshoe-shaped area rimming the Pacific Ocean. The Ring of Fire accounts for nearly 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes, caused by tectonic plates shifting and merging into and away from each other. Every year, Japan alone experiences around 1,500 earthquakes. Some earthquakes cause tsunamis— long, high, and sometimes very powerful sea waves.

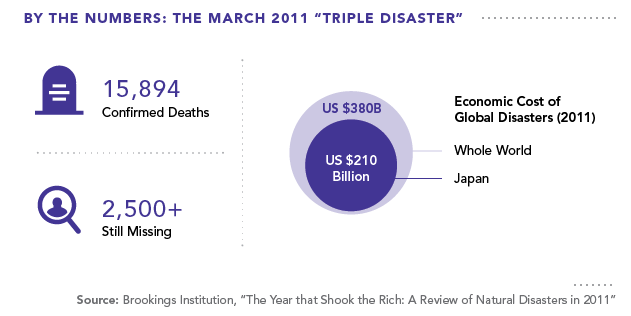

One of Japan’s worst natural disasters was the “Triple Disaster,” which started on March 11, 2011. It began with the 9.0 Tohoku Earthquake, sometimes called the Great East Japan Earthquake, off Japan’s east coast. The tsunami that followed reached 30 meters in some areas. It swept away houses, cars, telephone poles, and almost everything else in its path.

The tsunami waves also damaged the backup generators at the nearby Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, adding to the area’s long-term environmental damage. Scientists have called it the second-most significant nuclear incident in history (behind only the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine).

Figure 5: By the Numbers: The March 2011 “Triple Disaster”

Figure 5: By the Numbers: The March 2011 “Triple Disaster”

Despite the devastation of the Tohoku triple disaster, Japan is one of the most well-prepared countries in the world for earthquakes. Many of its buildings are designed to withstand large shocks. For example, skyscrapers are built to sway from side-to-side rather than collapsing during an earthquake. Preparation also includes human behavior. Japanese students participate in earthquake preparedness training every month, and most buildings and houses keep emergency earthquake kits on hand. Japan is also exploring ways to minimize the damage cause by tsunamis. Scientists are studying tsunami patterns so they can better predict and warn people about them.

As an archipelago, Japan is also susceptible to typhoons—tropical storms that can cause flash floods and landslides. The government has tried to mitigate the damage from typhoons by building dams and encouraging residents to move away from areas susceptible to floods. Other aspects of adaptability, however, are not so straightforward. Many rural Japanese homes are built from wood, which is ideal for an earthquake-prone country because wood is flexible enough to endure shaking. However, wood homes are not ideal for typhoons and landslides because they are more easily swept away than concrete buildings during floods.

What Does Japanese Pop Culture Teach us About Japan?

Japanese pop culture is a global phenomenon. Many millions of people around the world are eager consumers of Japan’s anime (animation), manga (comic books), and video games, as well as karaoke, karate, ramen noodles, sushi, Sudoku, and more. Some of these products are “odourless,” meaning they do not have an obvious association with Japanese culture. For example, using a karaoke machine does not necessarily make you more informed about Japan, nor does doing a Sudoku puzzle. In fact, some people might not even be aware that the products they’re using are Japanese.

However, some forms of Japanese pop culture do help us understand issues that have been on the minds of Japanese people. Historian William Tsutsui points to a few themes.1

Fascination with the apocalypse: This appears mostly in Japanese popular films, anime, and manga. Such a focus should not come as a surprise: Japan is the only country to have experienced atomic warfare, and also suffers from natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis. An early example of this theme is the 1954 movie Godzilla, or Gojira, in Japanese. In it, a 50-meter-tall “ancient monster, deformed by a series of nuclear bomb tests and expelled from his natural habitat, lands in Tokyo and starts destroying Japanese cities.”2 (Godzilla also touches on another theme in Japanese pop culture: monsters.) Over the years, Godzilla has been featured in dozens of films, both Japanese and Western. The original Japanese version was released less than a decade after the end of the Second World War/Pacific War, when memories of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the firebombing of Tokyo were still fresh in the memories of Japanese people. (The later American version of the film was edited significantly, removing anything that could have been seen as criticism of the U.S. and its post-War occupation of Japan.)

Human interaction with technology: This theme focuses especially on interaction with human-like androids, robots, and cyborgs. Several stories told through anime and manga explore the limits of what it means to be human and the possibilities of fusing human and machines.3 An early example is the 1952 manga (later an anime), Astro Boy. In this story, a scientist tries to fill the emotional hole left by the death of his young son. He does so by creating a humanlike android, named Astro Boy, to replace him. Although the father later concludes that his son cannot be replaced by a robot, Astro Boy lives on. Not only does he survive, but he learns how to control his powers and develops a conscience.

Figure 6: Video of "Astro Boy Episode 1"

A more recent example of this theme is the film Ghost in the Shell. (Canadians may be familiar with the 2017 re-make of the film, which was based on a 1995 anime.) In this story, the main character is a cyborg named Major Motoko Kusanagi. Her human brain, or soul, is the ‘ghost’ inside the ‘shell’ of a manufactured body. The body is owned by the government, and she works on behalf of Section 9, an anti-cyberterrorism task force. In the film, “She questions who she is, who she was, and what it even means to be human,” leading viewers to wonder: “If even your brain has been augmented by technology, are you still you?”

A love of cuteness (kawaii): This theme is prevalent not only in stories, but also in a wide range of material products and fashions. The most well-known example is Hello Kitty, which appears in cartoons, on t-shirts, and splashed across a wide range of accessories. In fact, kawaii does not mean just cuteness, but also an embrace of “childishness, vulnerability, smallness, and sweetness.”6 It appeals not only to Japanese children, but also adults, especially women (and some men). Some experts suggest that this embrace of kawaii is a way for Japanese young adults in particular to cope with the strict nature of work culture in Japan. Another example of kawaii is TarePanda, or “lazy” or “droopy” Panda. In fact, this character appeals to people, both men and women, because it depicts a creature that is tired, which is how many working-age Japanese people often feel.

The embrace of kawaii includes not just ‘stuff’ like clothes and pencil cases, but also behaviours, such as talking in the manner of a child. This is most common among young, unmarried women who are trying to hang on to the “simplicity, happiness, and emotional warmth” of childhood, rather than thinking about the heavy responsibilities of marriage and parenthood.7

Figure 7: Video: "Living the Anime Lifestyle"

What is notable about Japanese pop culture is that it is not just popular in Japan—there are millions upon millions of fans all over the world. That leads to some questions: When people outside of Japan consume its pop culture, are they engaging in the “odourless” versions, that is, without thinking much about what the products say about Japan? And, How would people in other countries, including Canada, relate to the themes mentioned above?

End Notes:

1 This discussion of themes is summarized from William Tsutsui, Japanese Popular Culture and Globalization, Key Issues in Asian Studies, Ann Arbor, MI: Association of Asian Studies, 2010.

2 Yoshiko Ikeda, “Godzilla and the Japanese after World War II: From a Scapegoat of the Americans to a Saviour of the Japanese,” ACTA Orientalia Vilnensia, Vol. 12, no. 1 (2011), p. 43.

3 Tsutsui, Japanese Popular Culture and Globalization, p. 21.

Multimedia

In the News

- AGING JAPAN IN THE AGE OF ROBOTS

- THE GEOGRAPHY OF JAPAN’S NATURAL DISASTERS

- WHAT DOES JAPANESE POP CULTURE TEACH US ABOUT JAPAN?

Teacher Resources

Overview

We invite teachers to share ideas for using these materials in the classroom, especially how they can be used to build the curricular competencies that are prioritized in the new B.C. curriculum.

By registering with us, you will be able to access the for-teachers-only bulletin board. Registration will also allow us to send you notifications as new materials are added, and existing materials are updated and expanded.

For the sign in/register section:

Please register below to access the teachers’ bulletin board, and to receive updates on new materials.

Sign-in/Register

Registration Info

We want parts of this section to be secure and accessible to teachers only. If you’d like to access to all parts of the Teacher Resources, please sign-in or register now.

Sign-in/Register