China's One-Child Policy

Overview

Download as PDFIn 1979, China introduced its controversial One-child Policy, which limited most families to having just one child (rural families could have two children if their first child was a girl). At the time, China’s leaders worried that the country’s large population would be a drag on economic growth and their efforts to raise living standards. In their minds, health care, education, and housing, not to mention natural resources like land and water, were too scarce to support so many people. They believed that to improve the quality of life in China, they had to control the quantity of people. And the only way they could do this, they argued, was by taking drastic measures.

Was the policy a success? It depends on who you ask. Supporters say it worked: since the late 1970s, China’s economic growth has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. That would not have been possible, they say, without controlling population growth.

But critics say the policy was unnecessary, and ultimately replaced one problem—too many people—with another—too few. Specifically, China now has too few females and will soon have too few young people. These imbalances are creating social tensions that will be difficult to un-do, even now that the one-child restriction has been replaced with a two-child policy. These tensions are felt at a very personal level, and are challenging long-held values in China about the importance of marriage, family, and children’s sense of duty to their parents.

The Curious Timing of the One-Child Policy

To understand why China introduced such a radical population-control policy, it helps to understand the broader context of the 1970s, starting with a dramatic change of leadership. Since 1949, China had been ruled by Mao Zedong, a strong and charismatic (and sometimes paranoid and destructive) leader. Under Mao, the pursuit of personal wealth was forbidden and severely punished because he saw this as undermining the Chinese Revolution’s egalitarian ideals.

But in 1978, two years after Mao died, a new leader emerged with a plan to take China in a very different direction. That leader, Deng Xiaoping, quickly introduced the Four Modernizations—of agriculture, industry, national defence, and science and technology—that would help China get rich. But according to Deng and his allies, China had a problem: too many people. An article in the People’s Daily reflects the government’s thinking at that time:

If we do not implement planned population control and let the population increase uncontrollably, rapid population growth is bound to put a heavy burden on the state and the people, cripple the national economy, adversely affect accumulation and State construction, the people’s living standard and their health and slow down progress of the four modernisations.1

Editorial, People’s Daily, 8 July 1978

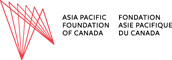

What is surprising is that the Chinese government even felt that such a strict population-control policy was necessary; after all, China’s fertility rate (the rate at which women have children) had been slowing for over a decade (see Figure 1), thanks to three main factors:

- Urbanization: After the Revolution in 1949, millions of people in China moved from the countryside to cities, eliminating the need for many couples to have a lot of children to help with farm work.

- Education of women: Under Mao, far more women received formal education and jobs outside the home, which made it less practical for them to have large families.

- Family planning policies: Even before the One-child Policy, the Chinese government had introduced the Later, Longer, Fewer campaign, which encouraged couples to wait longer to have their first child, allow for a longer period of time between the first and second child, and generally follow the government’s advice to have smaller families.

Figure 1: Dropping fertility rate in China, 1966-2013.

Figure 1: Dropping fertility rate in China, 1966-2013.

Why, if population growth was already slowing, did the government feel there was a need to impose such strict limits on the number of children per family? To date, there has been no clear explanation for this; however, we know the new leaders were under pressure to show that their economic reforms were improving the standard of living for Chinese people. We also know that they believed there was a strong link between population size and economic growth. Therefore, they may have concluded that they had no choice to but to lock in the lower fertility rates and reduce them even further.

One thing that is certain is that the government knew that many Chinese families would resist the One-child Policy. For that reason, it relied on both campaigns and persuasion, and on coercion for those who tried to break the rules.

Population Police, Punishment, and Propaganda

To enforce the One-child Policy, local officials in China often used invasive and sometimes violent measures. For example, the so-called “population police” monitored women’s fertility by subjecting them to regular physical exams. If they discovered that a woman was pregnant with a second child, she would often be forced to undergo an abortion. Many women were also forcibly sterilized to ensure they could not get pregnant again.

Some families defied the policy by having a second or third child. If the “population police” found out, they punished the parents by imposing fines that were well beyond most families’ ability to pay. Many such parents therefore kept their “above quota” children hidden from public view. Their official invisibility meant that these children were not given a residence permit, called a hukou, which meant they could not get health care, attend school, or even get a library card. It wasn’t until December 2015 that the Chinese government finally announced that 13 million of these hei haizi, or “black children,” would be allowed to register for a hukou.2

Punishment and coercion were not the only tools used. Peer pressure and an extensive propaganda campaign were aimed at persuading Chinese people to embrace the ideal of a one-child family. Most Chinese did not own a television, and cell phones and the Internet did not exist during the policy’s first two decades, so the government made use of public spaces to display slogans and images depicting happy, healthy, and prosperous one-child families (see Figures 2 and 3).

Video: "China’s secret children, the story of Li Xue" (2:37).

But punishment and coercion were not the only tools the government used. Peer pressure and a wide-reaching propaganda campaign were also launched to persuade Chinese people to embrace the idea of the small family. Most Chinese families did not own a television, and cell phones and the internet were not yet a reality – so the government made use of public spaces to display propaganda slogans and images depicting happy, healthy and prosperous one-child families (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Propaganda: “Prioritize family planning for the sake of development”.

Figure 2: Propaganda: “Prioritize family planning for the sake of development”.

Figure 3: Propaganda: Sculpture in Beijing promoting China’s One-child Policy.

At the heart of this propaganda were two basic messages. The first encouraged people to think about the broader national good, namely, that a smaller population would support China’s economic development efforts. The second focused on how small family size would benefit families themselves. For example, small families were portrayed as being ‘modern,’ and having only one child would allow parents to invest more in that child’s education to help him or her succeed in an increasingly competitive global economy. This second type of appeal was especially effective; by the 1990s, many urban families in China had more or less come to accept the idea of having only one child.

Unintended Consequences

Although the Chinese government claims the One-child Policy was a success, for years experts had warned that the policy had gone too far and was leading to unintended consequences that would be hard to un-do.

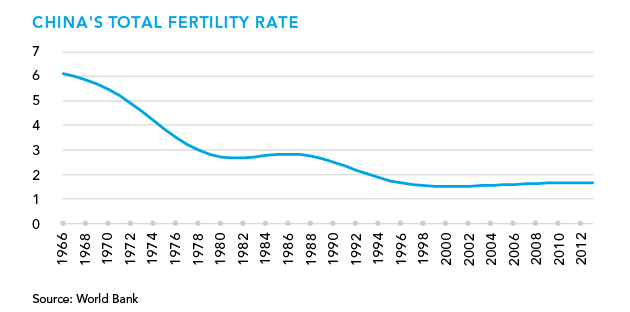

A top-heavy population pyramid: Typically, as countries develop economically, two things happen. The first is a drop in fertility rates, meaning fewer young people. The second is a rise in life expectancies as people have better access to health care and nutrition, meaning more old people. When these two trends are added together, the result is a shrinking number of young, working-age people having to bear the cost of caring for an expanding number of older, non-working people (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: China's population pyramids: 1960, 2015, 2050.

Figure 4: China's population pyramids: 1960, 2015, 2050.

Many wealthy countries like Canada have well developed social welfare systems to help support an aging population. But such a system is not well developed in China; that responsibility still falls primarily on younger family members. In fact, some young adults in China who are single children face the possibility of having to support two parents and up to four grandparents, a situation referred to as the “4-2-1 problem” (see Figure 5). In an attempt to assure that young people honoured this responsibility, the government introduced the “Elderly Rights Law” in 2013, essentially making it illegal to ignore the old people in your life.3

Figure 5: The “4-2-1 problem”.

Figure 5: The “4-2-1 problem”.

“Little Emperors” and expectation inflation: At a more personal level, the One-child Policy has changed life for only children. Some say these children are able to benefit from so much of their parents’ and grandparents’ attention. Also, only children can have opportunities to do things they might not be able to do if the parents had to pay for more than one child.

Audio: China’s ‘Little Emperors’ lucky, yet lonely in life (5:21)

But the media in both China and Western countries have not always been kind to these only children, referring to them as “Little Emperors” who are spoiled and have difficulties dealing with hardship because they are used to getting their way. Some say these children live a life of loneliness without siblings and cousins. Many are also under intense pressure to meet their parents’ high expectations that they will do well in school and get a prestigious and high-paying job in the future. In fact, the pressure from parents gets more and concentrated because they only have the one child on which to project their expectations.

Author Liu Yi describes the situation as follows:

"We are the unfortunate ones, because we are only children. Fate destined us with less happiness than children from other generations. We are also the lucky ones — with attention from so many adults, we skip over childish ignorance and grow up. Simple-minded, we are unable to see the realities of life, and the lack of burdens denies us depth."4

Liu Yi, I Am Not Happy: The Declaration of an 80s Generation Only Child

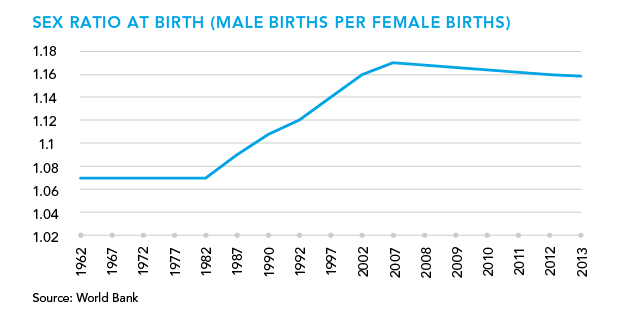

Too few girls: While many Chinese families eventually abandoned the traditional preference for large families, another tradition has been more stubborn: the preference for boys over girls. In the past, when a man in China got married, his wife became part of his family and the couple was expected to care for the husband’s parents in their old age. Although this practice has loosened in recent years, for at least two decades after the start of the One-child Policy, many parents opted to abort female fetuses in the hopes that the next child would be a boy. Because of this, China now has one of the most skewed gender imbalances in the world (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: China’s gender imbalance, 1962-2013.

Figure 6: China’s gender imbalance, 1962-2013.

This imbalance has become a source of social tension now that children born under the One-child Policy have reached the age of marriage. By most estimates, there are currently 35 million more young men than women in China. These men face a lot of pressure to get married and have a child so that they can continue their family line. But this has become more and more difficult for them to do, partly because there are just fewer women than men, and partly because many young women have become ‘pickier’ in choosing a husband. For example, some say they will not consider marrying a man if he cannot provide a nice apartment, a car, and a hukou (residence permit) in a big city like Beijing or Shanghai. That means that poor, rural, and less educated young men have been impacted most severely.

China’s Two-Child Future?

The announcement in late 2015 that China would transition to a two-child policy may not end up being the dramatic change that some made it out to be. For one thing, it is still the Chinese government, not Chinese people themselves, that has the final say in the size of families. In addition, despite all the outside experts who say the One-child Policy has created a “looming crisis” of gender and age imbalances, China’s leaders still insist that some form of population control policy is needed. The current president, Xi Jinping, recently said:

For some time in the future, China’s basic national condition of a large population will not fundamentally change. It will continue to put pressure on economic and social development. Tensions between the size of the population and resources and environment will not fundamentally change.

“Xi Says Family Planning to Remain a Long-Term Policy,” Global Times, May 19, 2016

Finally, the jury is still out on how Chinese people will respond to this loosening of the rules. One of the side-effects of the old policy is that there is now an expectation that parents will spend so much money and resources on a child, that even many middle class couples say they cannot comprehend being able to afford two children.5 China therefore may continue to have a generation of children who feel either lucky or lonely, or both.

End Notes:

1 Quoted in Cross, Elisabeth, “Introduction: Fertility Norms and Family Size in China” in China’s One-Child Family Policy, Elisabeth Croll, Delia David and Penny Kane (Eds.), New York: St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1985, p. 26.

2 Zhu Xi, “President Xi Jinping: China to Register 13 Million ‘Black Children’ without ‘Hukou,’” People’s Daily Online, December 10, 2015.

3 Celia Hatton, “New China Law Says Children ‘Must Visit Parents,’” BBC News, July 1, 2013,

4 From Liu Yi, I Am Not Happy: The Declaration of an 80s Generation Only Child, as quoted in Louisa Lim, “China’s ‘Little Emperors’ Lucky, Yet Lonely, in Life,” NPR News, November 24, 2010,

5 Did Kirsten Tatlow, “One ‘Child’ Culture Is Entrenched in China,” New York Times, November 4, 2015,

Multimedia

Quizzes

-

China's One-Child Policy

Think you know the who, what and why of China’s One-child Policy? Take this quiz to find out!

Start Quiz -

China's One-Child Policy - 1 of 4

SubmitChina’s fertility rate dropped significantly starting around 1970. The One-child Policy was the most significant factor in reducing China’s fertility rate.

TrueFalse -

China's One-Child Policy - 2 of 4

SubmitWho was the leader of China when the One-child Policy was implemented?

-

China's One-Child Policy - 3 of 4

SubmitWhat is the informal name used to describe local officials who monitor women’s fertility?

Population police4-2-1 Brigade“Black children” -

China's One-Child Policy - 4 of 4

SubmitThe “4-2-1 problem” refers to the burden that many children face having to care for two parents and up to four grandparents. The Chinese government has made it illegal for adult children to shun this responsibility.

TrueFalse -

China's One-Child Policy - Results

Your score: out of 4 Correct!Take it Again

In the News

- Western News

- Chinese News

Audio

One-Child Policy

Deng Xiaoping

"Black Children"

Little Emperor

Teacher Resources

Overview

We invite teachers to share ideas for using these materials in the classroom, especially how they can be used to build the curricular competencies that are prioritized in the new B.C. curriculum.

By registering with us, you will be able to access the for-teachers-only bulletin board. Registration will also allow us to send you notifications as new materials are added, and existing materials are updated and expanded.

For the sign in/register section:

Please register below to access the teachers’ bulletin board, and to receive updates on new materials.

Sign-in/Register

Registration Info

We want parts of this section to be secure and accessible to teachers only. If you’d like to access to all parts of the Teacher Resources, please sign-in or register now.

Sign-in/Register