Asia Profiles: Mongolia

Overview

Download as PDFMongolia is a landlocked country between Russia to the north and China to the south. It sits on a large plateau, and almost 80 percent of its land is grassland. Other features include the Gobi Desert in the south-southeast, the Altai mountains in the west- southwest, and the Khangai mountains near the centre. The country’s weather is extremely varied; during the winter, temperatures commonly reach -40°C, while in the summer they can reach as high as +40°C.

Map 1: Mongolia.

Basic Facts

- Population: 3,068,243

- Life Expectancy: 69.9 years

- Literacy Rate (age 15 and over can read & write): 98.4%

- Official and Major Language(s): Mongolian 90% (official) (Khalkha dialect is predominant), Turkic, Russian

- Type of Government: Semi-presidential Republic

- Current Leader: President Khaltmaa Battulga

Internet and Social Media

- Active Internet Users: 65% of population

- Average Daily Internet Use: Not available

- Active Social Media Users: 65% of population

- Average Daily Social Media Use: Not available

Economy

- GDP: C$14.46 billion

- GDP per capita: C$4,727

- Currency: Mongolian Tugrik

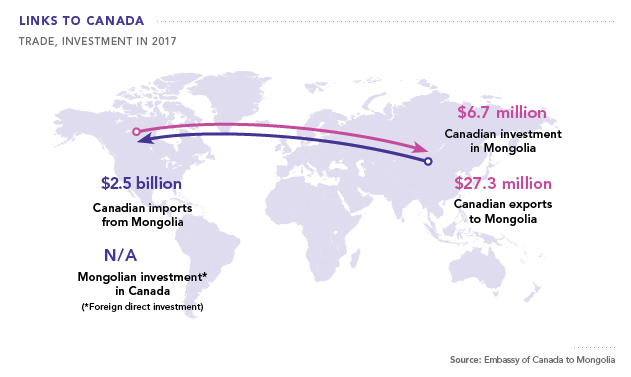

Exports: copper, apparel, livestock, animal products, cashmere, wool, hides, fluorspar, other nonferrous metals, coal, crude oil

Imports: machinery and equipment, fuel, cars, food products, industrial consumer goods, chemicals, building materials, cigarettes and tobacco, appliances, soap and detergent

Climate Change’s Threat to a Cherished Way of Life

When people picture Mongolia in their minds, they often see three things. One is its vast, green fields with rolling hills and not a car or telephone pole as far as the eye can see. Another is the round tents, called a ger (also called yurts), that house many rural Mongolian families. And a third is the herds of animals—sheep, goats, cattle, horses, yaks, and camels—which are the livelihood of many of these families. These are among the defining features of life for one-third of Mongolia’s three million people who live as pastoral nomads.

However, many Mongolians are being forced to leave that traditional way of life behind. A major culprit is a weather pattern called a dzud (the ‘d’ is silent, and the word rhymes with ‘bud’). A dzud is a hot, dry summer followed by a long, cold winter when temperatures can get as low as -46 degrees Celsius. During a dzud, not enough grass grows to feed the animals. If the animals don’t get enough to eat, they don’t have enough fat to protect them from the cold, and are not healthy enough to reproduce. The 2009 dzud was especially severe: an estimated 9.7 million animals died that year.

Although dzuds are not a new weather phenomenon, many scientists believe that climate change is making them more frequent and more intense. Historical records show that in the eighteenth century, there were 15 dzuds, in the nineteenth century, there were 31, and in the twentieth century there were 43. According to Professor Alison Hailey Hahn, “While dzuds were once predicted to occur every eight to twelve years, they are now expected every other year.”

Many pastoral Mongolians keep their wealth not in bank accounts, but in the value of their animals. Therefore, a significant loss of their livestock can be economically devastating. How are Mongolia’s herding families coping with the hardship caused by the dzuds? Some try to pool their resources, like emergency supplies of animal food, with other herding families. Some seek help from international aid organizations. And some are trying to use technology to get advance warning of when a dzud is approaching.

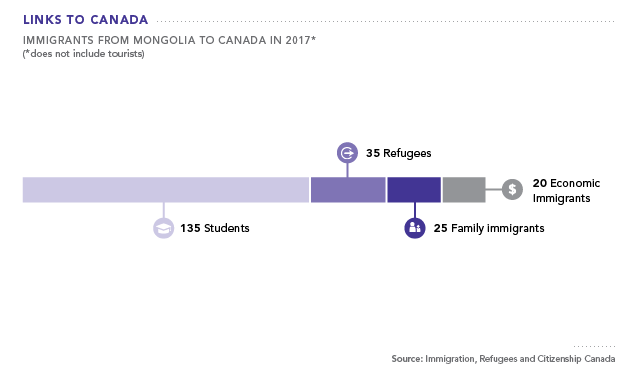

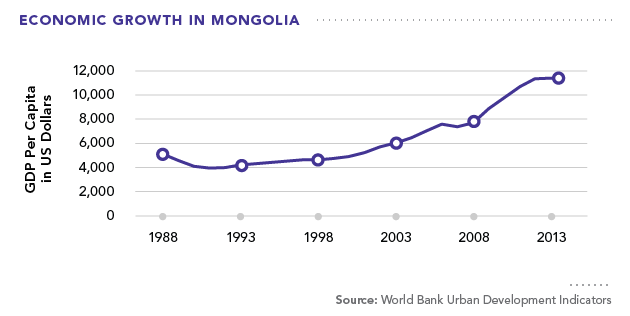

Figure 1: Urban Population in Mongolia and Ulaanbaatar

Figure 1: Urban Population in Mongolia and Ulaanbaatar

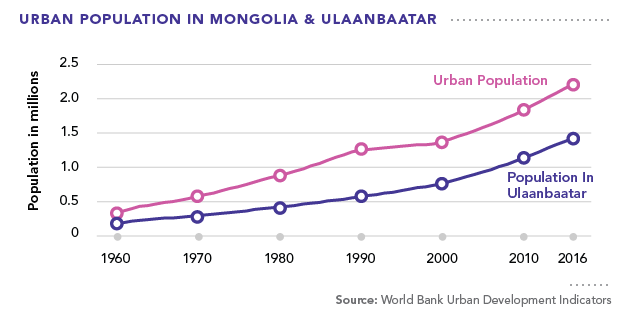

Figure 2: Sources of Air Pollution in Ulaanbaatar in Winter

Figure 2: Sources of Air Pollution in Ulaanbaatar in Winter

Other families, however, are packing up and moving to the city. In fact, many have moved to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital city. Oftentimes, they take their ger with them and set it up on the city’s outskirts. The conditions in many of these unplanned suburban ger areas are not good, as many lack indoor plumbing and electricity. To generate heat in the winter, they often burn whatever they can find—raw coal, paper, garbage, or old tires. This has made the air quality in Ulaanbaatar among the worst in the world. Ironically, this practice contributes further to climate change. And even more ironically, it is the bad air quality that is now causing some of these rural-to-urban migrants to consider moving back to the countryside.

The True Costs of Cashmere

Cashmere is synonymous with luxury. Items made from this soft-to-the-touch material, like sweaters, coats, and shawls, can sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars. That should be good news for Mongolia, the world’s second-largest producer of raw cashmere (a distant second behind China). Its cold, harsh weather is ideal for raising cashmere goats. In winter, these animals grow an undercoat of fine hairs to stay warm. When the weather gets warmer, these hairs get brushed out by herders. The herders then clean and sort the fibers before selling them to a buyer, who turns the material into a finished product. One reason these finished products are so expensive is that it takes several ‘brushings’ to produce just one item. For example, it takes the fleece of four to six goats to make one sweater, and the fleece of 30 to 40 goats to make one overcoat.

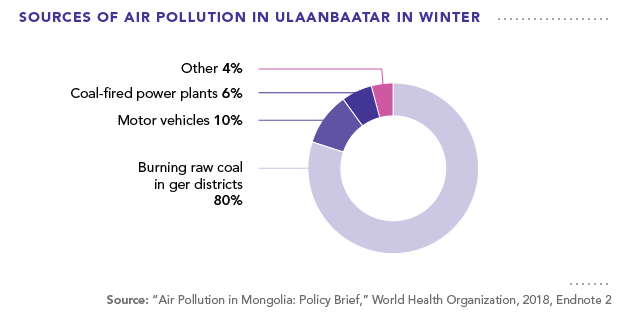

Figure 3: Economic Growth in Mongolia

Figure 3: Economic Growth in Mongolia

Mongolia’s cashmere production began to grow rapidly in the early 1990s. On one hand, this has been good for the economy—cashmere is Mongolia’s third-largest export, after copper and gold. On the other hand, the growth of this industry has had serious environmental side effects that could threaten the future of the business. Why did this industry grow so rapidly, and how can these negative side effects be minimized?

Mongolia’s “Dual Transition”

From 1921 to 1990, Mongolia was ruled by a socialist government that conducted top-down, centralized economic planning. During this period, almost all of its exports went to other socialist governments. In fact, most of Mongolia’s raw cashmere was sold to Eastern Europe. Then, in 1990, Mongolians overthrew their socialist government in a non-violent revolution, just as socialist governments were also collapsing in other countries. That set Mongolia on a “dual transition”—from an authoritarian government to a democracy, and from a state-controlled, centrally planned economy to a market economy. These transitions can be painful, especially the economic part. Once the old economic system is dismantled, the country needs to act quickly to encourage new businesses. These businesses can help absorb the people who are suddenly unemployed by the end of socialism.

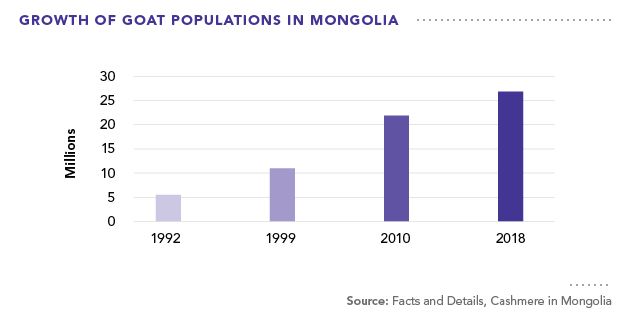

Mongolia was no different. Given its competitive advantage in producing raw cashmere, it was logical for the new government to encourage the growth of that industry. In the mid-1990s, it privatized 90 percent of the cashmere goat herds.1 That meant that people were now free to go into the business. The resulting increase was dramatic. In 1992, Mongolia had around 5.5 million goats. By 1999, that number had doubled to around 11 million. A decade later, in 2010, it had doubled again, to around 22 million. As of 2018, that number had climbed to 27 million goats. Some of this increase came from existing herders adding more goats to their herds. Another part of the increase came from new people entering the business, especially those who had lost their jobs after the end of the socialist economy.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Although the “dual transition” was difficult, especially in the early years, Mongolia’s economy began growing steadily by the late 1990s. The cashmere industry played an important role in providing income and employment to many Mongolians. However, there are concerns that the business is becoming a victim of its own success. The large increase in the goat population is putting considerable stress on the pasturelands where these and other animals graze. Mongolia’s landmass is about 70 percent pastureland, and about 70 percent of that pastureland is showing signs of degradation. This is the result of a couple of things. One, of course, is too many goats grazing on a fixed amount of land. Another is the physical properties and habits of the goats themselves—they have sharp hooves that cut through the topsoil, and they eat plants from the roots up. Both of these make it difficult for the grasslands to recover and replenish themselves. This degradation is leading to desertification. The impacts of desertification are both serious and widespread, and include loss of productivity of the land, a scarcity of wood for fuel and building material, a decrease in water supplies (especially groundwater), an increase in flooding when it rains, and an increase in air and water pollution from dust and sedimentation.

Figure 4: Growth of Goat Population in Mongolia

Figure 4: Growth of Goat Population in Mongolia

Responsible Luxury?

One possible solution to desertification in Mongolia is to shrink the total number of goats being raised for cashmere. One expert proposes reducing the total number of goats to 10 million, a significant reduction from today’s numbers. This would have a positive environmental impact, but it would be difficult for herders to accept the loss of an importance source of income. This is especially true for those with smaller herds who feel they can’t afford to make that sacrifice.

There are also questions about whether consumers of cashmere bear any responsibility for Mongolia’s environmental challenges. For example, one of the more recent trends in global cashmere sales is cheaper items—sweaters that sell for $50, instead of $500, for example. These are made from lower-quality cashmere, but the goats that produce this lower-quality material have the same environmental impact as goats that produce higher-quality material. So, when shoppers in Canada and other countries are thinking about buying a low-cost cashmere product, they should ask themselves not only what it will cost them, but what the true cost is, including to the people and the environment in Mongolia.

Mongolia’s Gender Gap

The term “gender gap” refers to differences in the attitudes, opportunities, and status for men and women. One type of gap is education, which is usually measured by years of schooling for boys vs. girls. Another type of gap is employment. This includes the percentage of working-aged men and women who participate in the labour force (that is, hold jobs outside the home), and whether they receive similar levels of pay. In theory, these gaps are related—the more formal education and training a person has, the more likely she or he will get a stable and well-paying job. However, as can be seen in the case of Mongolia, the relationship between education, employment, and pay is not so straightforward.

Mongolian boys and girls complete primary school and the early years of high school at almost the same rates. When they reach the upper years of high school, things start to diverge. This is especially true in rural areas. In many other countries, it is common for families to keep their sons in school to finish their high school education, while keeping their daughters at home to help with housework or to care for younger siblings. Sometimes, teenage girls leave school to get full-time jobs to support the family finances. In Mongolia, the trend is the reverse; more Mongolian women than men complete high school and college or university.

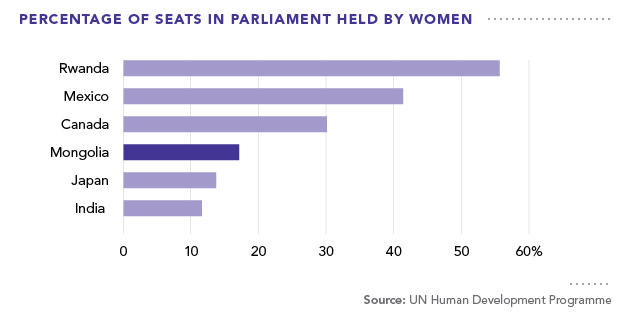

Figure 5: Percentage of Seats in Parliament Held by Women.

Figure 5: Percentage of Seats in Parliament Held by Women.

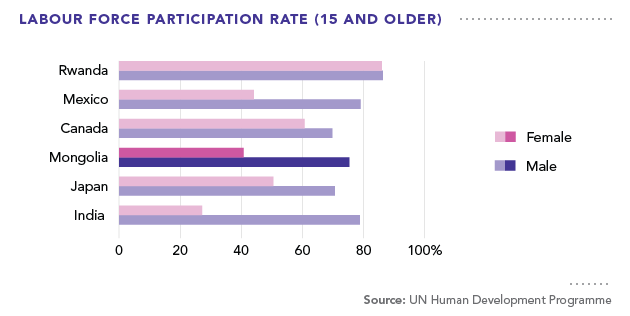

According to a recent report by the World Bank, this extra education gives Mongolian women “income-generating characteristics”—in other words, the types of knowledge and skills that should get them better jobs with better pay. Yet Mongolian women’s participation in the labour force is lower than it is for men. In 2017, the labour force participate rate was 66 percent for men, but only 53 percent for women. Their average salaries are also lower. In 2015, the average annual salary for men was about US$4,200. For women, it was US$3,720.

What explains these differences, especially since Mongolian women are more educated? And why do such gaps persist in Mongolia and in other societies? One explanation is based on the idea of merit—a person’s opportunities and status are a result of their individual abilities, choices, and effort. Another explanation is based on the idea of that opportunities and status are based not just on merit, but also on attitudes and stereotypes that might lead to discrimination (in most cases, it is discrimination against women).

In the case of Mongolia, the second explanation seems more accurate. According to a recent media report, parents in rural Mongolia want their sons to help the family with herding animals. They view this work as “men’s work” that does not require additional schooling. This work is not always stable and predictable, though, because it depends on factors that can’t be controlled, like the weather or environmental conditions. Therefore, these families invest more in their daughters’ high school and university or college education. They do so in hopes that their daughters will get well-paying white collar jobs, such as working in an office, hospital, or school. That is reassuring for parents because they believe that their daughters will take better care of them in their old age than their sons.

However, after they complete their education, many Mongolian women face challenges that make it difficult for them to reach the same status or pay level as men. One of the reasons is that many of them are expected to take care of their parents, as well as their husbands and children. Because they have these extra responsibilities, some employers might perceive them as being less available to work, or less reliable if they have to stay home to care for sick children. Therefore, it is not that women are not working, but rather that much of their work is “informal” or unpaid work that is done in the home.

Figure 6: Labour Force Participation Rates (15 and Older)

Figure 6: Labour Force Participation Rates (15 and Older)

Another important gender gap dimension is political empowerment. One way to measure this is by looking at the percentage of seats in a country’s parliament that are held by women. Here, too, it is rare for women to crack the 50 percent threshold, despite being 50 percent of the population. The under-representation of women in political decision making may partly explain why other types of gender gaps persist. Maybe if more women were in decision-making roles, they would make policies that ensure that women are fairly compensated for their education, training, and work.

End Notes:

1 The government did this with some reluctance, but it was facing pressure by international development banks to adopt market principles. At the time, Mongolia badly needed development assistance from these banks, so it agreed to do so.

Multimedia

In the News

- CLIMATE CHANGE IN MONGOLIA

- MONGOLIAN CASHMERE

- GENDER GAP IN MONGOLIA

Teacher Resources

Overview

We invite teachers to share ideas for using these materials in the classroom, especially how they can be used to build the curricular competencies that are prioritized in the new B.C. curriculum.

By registering with us, you will be able to access the for-teachers-only bulletin board. Registration will also allow us to send you notifications as new materials are added, and existing materials are updated and expanded.

For the sign in/register section:

Please register below to access the teachers’ bulletin board, and to receive updates on new materials.

Sign-in/Register

Registration Info

We want parts of this section to be secure and accessible to teachers only. If you’d like to access to all parts of the Teacher Resources, please sign-in or register now.

Sign-in/Register