Asia Profile: Bangladesh

Overview

Download as PDFMuch of Bangladesh’s terrain is flat and lies less than 10 meters above sea level. It is also one of the wettest countries in the world, with monsoon rains and frequent floods from June to September. The flooding is both a blessing and a curse—the floods deposit silt, which makes the farmland more fertile, but they also cause serious damage. The climate is tropical-monsoon, which means hot, rainy summers and dry winters. The country lies within the delta formed by three major rivers—the Brahmaputra, the Ganges, and the Meghna.

Basic Facts:

- Population: 159,453,001 (percentage under 25 years: 48%)

- Life Expectancy: 74 years

- Literacy Rate (age 15 and over can read & write): 73%

- Official and Major Language(s): Bangla/Bengali (99%), other (1%)

- Type of Government: Parliamentary republic

- Current Leader: Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina

Internet & Social Media

- Active Internet Users: 55% of population

- Average Daily Internet Use: No data

- Active Social Media Users: 20% of population

- Average Daily Social Media Use: No data

Economy

- GDP: $916.7 billion

- GDP per capita: $5,587

- Currency: Taka

Exports: garments, knitwear, agricultural products, frozen food (fish and seafood), jute and jute goods, leather

Imports: cereals, pulses, iron & steel, oilseeds, fertilizer, precision and technical instruments

Bangladesh and Lessons for Adapting to Climate Change

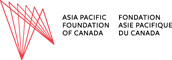

Bangladesh has been described as a ‘laboratory’ for learning about how people and communities will be affected by climate change. For one thing, its geography makes it one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to the impacts of climate change. For another, Bangladesh has a high population density, which means the number of people who will be impacted will be very large.

Some people describe Bangladesh as another kind of laboratory—one where other countries can learn about how people and communities can adapt to climate change. Understanding what adaptation looks like starts with asking a few questions: What do different models of climate change adaptation look like? What are the benefits and challenges of each model? Finally, who should pay for the costs of adaptation?

The Blessing and Curses of Geography

In some ways, Bangladesh’s geography is a blessing. Its land is criss-crossed by three major rivers—the Brahmaputra, the Ganges, and the Meghna. These rivers’ deltas make much of the soil fertile and thus good for farming. Farming is a livelihood that employs nearly half of the labour force in Bangladesh. In other ways, however, the country’s geography is a curse. Its location puts it in the path of powerful cyclones. These storms bring heavy rainfall, which floods the rivers and endangers the people who live near the river banks. In addition, Bangladesh’s coastlines are affected by storm surge—water pushed ashore by strong storm winds. Many climate experts believe that global warming, specifically, the rising surface temperature of the Indian Ocean, is making these storms more frequent and more intense.

Bangladesh’s low elevation is another challenging aspect of its geography. About two-thirds of the country’s land is less than five metres above sea level. This low elevation makes the coastal areas vulnerable to two other aspects of climate change: sea-level rise and coastal erosion. These two impacts are hitting farmers especially hard. Sea water has begun to intrude into fresh water sources, contaminating the drinking water for the farmers, as well as for the crops and animals they raise.

What can people do when their communities and livelihoods are negatively impacted in these ways by a changing climate?

Adaptation in Place

Some communities in Bangladesh are experimenting with ‘adaptation in place’—making changes to physical infrastructure, and sometimes to human activities, to avoid people having to leave a climate-impacted area. For example, one village in Bangladesh discovered that saltwater intrusion was negatively impacting its ability to grow rice, which requires fresh water. The villagers switched from growing rice to raising prawns and fish that can live in salt water. In another case, people left their village and moved to a nearby area that had not yet been as seriously impacted by climate change.

In other cases, adaptation in place might require more extensive changes. For example, some communities might need to physically build up the land on which they live to deal with sea-level rise and coastal erosion. They might also have to elevate their houses, outdoor toilets, and the shelters for farm animals so that these things do not get washed away by floodwaters.1

The people who would benefit from these changes are mostly poor farmers who cannot pay the high costs of such large-scale changes. The responsibility to pay for them would therefore fall to the government or international aid agencies. Given that Bangladesh is a poor country, should money be spent to support these kinds of adaptation in place? Do people have a basic right to remain in their homes and communities, no matter what the cost? Or, would this money be better spent on other basic needs for poor people, like education and clinics?

Climate-Induced Migration

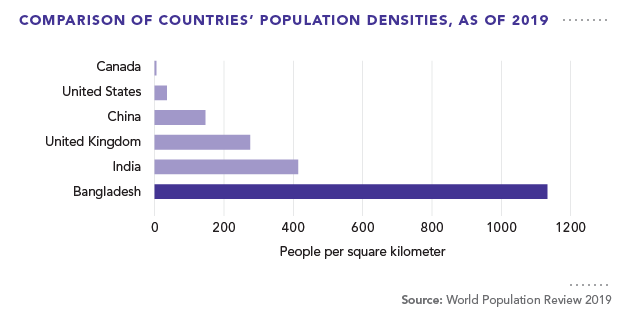

Another type of adaptation is climate-induced migration. This means people permanently leaving an area impacted by climate change and moving to another part of the country. One report estimates that climate change may create more than 13 million climate migrants in Bangladesh over the next 30 years.2 Some experts think that number could be much higher.

Usually, people in Bangladesh migrate from rural areas to cities for economic reasons, such as looking for a better-paying job. They often have little money and few possessions. Also, farming does not prepare them well for a lot of urban jobs. Therefore, they often have to take work that is difficult, dangerous, and low-paying. One environmental expert painted a bleak picture of what life could be like for many of these migrants.

“When they get to cities, they will be forced to live in shantytowns and other ‘irregular settlements,’ in shacks often built on precarious land in floodplains, subject to mudslides, extreme heat, and unsanitary conditions. They will be forced to work in the informal sector, earning pennies and living hand-to-mouth.”3

This does not have to be the fate of Bangladesh’s climate migrants. The government could create programs to provide better education, health care, and job training for them either before or after they arrive in cities. It could also invest in building housing that climate migrants can afford.

As in the case of adaptation in place, many of these programs will cost a lot money. Should a poor country like Bangladesh be expected to pay for these changes itself? Or do other countries have a responsibility to help?

The Unfairness of Climate Change

Saleem Huq, a climate change expert from Bangladesh, described the unfairness that is at the heart of climate change’s causes and impacts. He said:

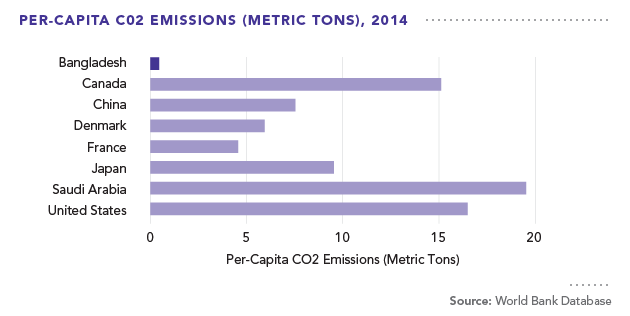

One group of people—namely, those who consume the most, particularly in wealthier countries—have caused the problem, and another group—namely, poor people, especially in poorer countries—will suffer the brunt of the adverse consequences in the near term.4

Bangladeshi people have been among the lowest emitters of C02, a major contributor to climate change. But they are already suffering from some of the most serious consequences. In contrast, some of the biggest per-capita (per-person) emitters have been far less impacted. What responsibility do these high-emitting countries have? Mr. Huq and others have argued that they have a responsibility to radically reduce their C02 emissions, and to compensate people in climate-impacted countries for the damage that has already been caused, and will be caused.5

Some countries and international organizations are stepping up to provide such assistance. However, given the scale of the problem in Bangladesh and the number of people impacted, it is not yet clear whether this assistance will be enough. The ‘laboratory’ of Bangladesh may also provide lessons in what happens when countries and governments do or do not work together to help people adapt to one of the future’s biggest challenges.

Bangladesh Pays a High Price for Fast Fashion

On April 24, 2013, people reported to work as usual at the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The building contained several factories that made clothes for the country’s garment industry. Shortly after 9:00 a.m., the building collapsed. The causes of the collapse were poor building construction and violations of safety codes. The day before, workers had alerted their supervisors when they noticed deep cracks appearing in the walls. The supervisors ignored their concerns and ordered them back to work. It was a very costly mistake: 1,134 people died in the collapse and more than 2,500 were injured. Some lost limbs or had other injuries that were so severe that they couldn’t return to work.

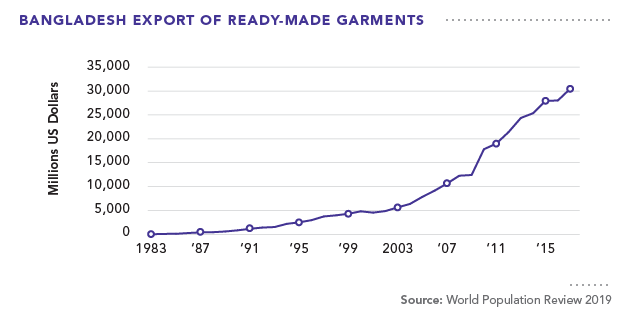

Most of the items made in Bangladesh’s garment factories get sold in foreign countries, in stores like Wal-Mart, The Gap, H & M, Joe Fresh, and others. These stores are part of the ‘fast fashion’ trend. Fast fashion refers to clothes that are made cheaply and quickly to meet two customer demands: low prices and a continuous supply of new styles. Fast fashion has grown immensely since the 1990s, when globalization encouraged businesses to move part of their operations overseas. Many companies did so, taking advantage of low wages in other countries to lower their production costs. Consumers in countries like Canada benefit from the globalization of garment production through lower prices. Does it also connect them more closely to the safety and welfare of the people who make the clothes?

The Good and the Bad of Bangladesh’s Garment Industry

Bangladesh is an attractive place for the global garment industry. It is poor and has low average wages. It also has a large population of working-age people available to do labour-intensive tasks like sewing, ironing, cutting, and inspecting clothes before shipping them off for export. Because of these advantages, the country’s garment industry is the second-largest in the world, behind only China’s.

In some ways, the global garment industry has been good for Bangladesh. It has created millions of jobs, which has helped reduce the number of people living below the official poverty line—from about 44 per cent in 1991 to less than 13 per cent today. Eighty per cent of the factory workers are women. For young women in particular, a job in a garment factory provides one of the few opportunities they have to become financially independent of their parents. Also, if they send part of their earnings back to their families (as many of them do), their parents are less likely to pressure them to quit work and get married at a young age.

However, this industry has a dark side. Many factory buildings are unsafe. The risks for workers include collapsing buildings (as was the case with Rana Plaza), fires, injuries from heavy equipment, and exposure to dangerous chemicals. Also, workers are often forced to work long hours—as many as 15 hours a day, six days a week. If they refuse or complain to their bosses, they could get fired. For all of these sacrifices, they earn as little as US$ 32 cents an hour.

Why are these conditions so poor? And who should be responsible for improving them?

A Shared Responsibility?

In the days and weeks after the Rana Plaza disaster, people in Bangladesh and around the world began asking who was to blame for such a senseless and avoidable tragedy. Many people blamed the factory owners, accusing them of prioritizing their own profit over worker safety. Some even called for a boycott of clothes made in Bangladesh. But the factory owners pointed to the foreign clothing companies. They said the prices these companies were willing to pay were too low to cover the cost of safety upgrades and higher wages for workers. They also said their workers had to work long hours because of companies’ insistence on short lead times—that is, companies placed their orders and expected the clothes to be finished in a very short period of time. These two pressures have been called the ‘price squeeze’ and the ‘lead time squeeze.’

Labour rights and human rights organizations also weighed in on the debate. They said factory owners and foreign clothing companies both had a responsibility to do better. They also said some of the responsibility should be borne by people who shop at fast fashion stores. These consumers, they said, have a moral duty to care about who made their clothes and under what conditions.

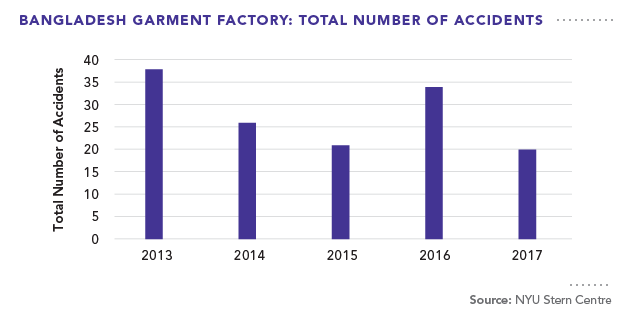

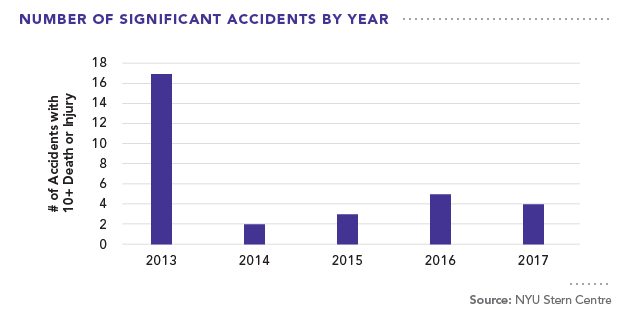

The Garment Industry’s Mixed Record

Rana Plaza raised awareness of the real cost of cheap clothes – low pay, long working hours, and unsafe working conditions. It also revealed that many of these workers, including those at Rana Plaza, had not formed unions to advocate for their rights. Did this awareness lead to changes in Bangladesh’s garment industry? The record so far is mixed.

One of the most important changes was to factory safety. In the weeks after Rana Plaza, more than 200 foreign companies formed two international agreements: the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, with more than 180 members, mostly from Europe; and, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, with more than 25 members from the United States and Canada. The participating companies agreed to conduct safety inspections in all of the 2,300 factories that supplied them (about 60 per cent of Bangladesh’s garment factories). If they found safety violations, they would help the factories fix the problems. These safety upgrades impacted more than 2.5 million workers.

In other areas, however, there has been less progress. In 2013, the year of the Rana Plaza disaster, the minimum wage for garment workers was around US$40 a month. In the years after the disaster, it was raised to US$63 dollars, then raised again in 2018 to US$95. Nevertheless, Bangladesh’s garment workers are still among the lowest paid in the world, and many of them live just barely above the official poverty line. Also, an investigative report found that lead times had actually gotten shorter, decreasing more than eight per cent from 2011 to 2015. The result is that many workers are still required to work long hours with few rests.6

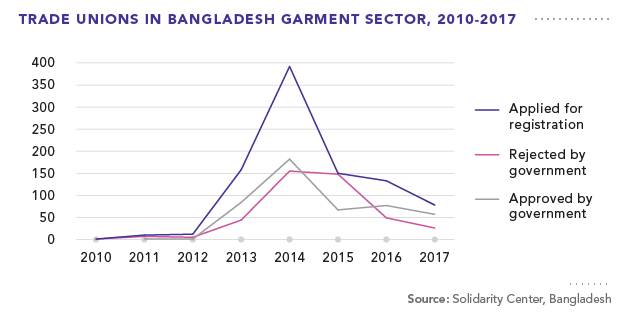

Progress on union formation is also a mixed picture. The registration and approval of new unions spiked in the year after Rana Plaza. Also, thousands of union leaders were trained in how to detect and address fires and other hazards. However, after peaking in 2014, union registrations and approvals dropped to pre-Rana Plaza levels.7 According to one labour rights organization, 445 garment factories in Bangladesh have trade unions, which is only about 11 per cent of all garment factories.

Does More Information Lead To Change?

Another important change that came out of the Rana Plaza tragedy was a demand for more information and transparency about where and how clothing is made. For example, the Clean Clothes Campaign, a group of trade unions and other grassroots organizations, regularly monitors working conditions for garment workers in Bangladesh and other countries. And in 2018, a charity called Fashion Revolution launched the Fashion Transparency Index, which provides information about the social and environmental practices of the world’s biggest fashion brands. They believe that if consumers have this information, they will change their shopping habits.

However, it is not clear whether this information is changing the basic conditions for garment workers. The demand for fast fashion continues to grow; according to one media report, fast fashion grew 21 per cent from 2016 to 2019.8 In some cases, clothing prices are going down, not up. For example, Bangladesh’s main export to the United States is men’s and boys’ cotton trousers. The price of these items is now 13 per cent less than before Rana Plaza. Similarly, Bangladesh is the largest supplier of T-shirts to Europe. Europeans are paying about five per cent less than five years ago.9 That has caused many to wonder if the post-Rana Plaza changes are just temporary, and whether the power to change things ultimately rests with consumers. As one journalist commented, “If Rana Plaza is to be a turning point, we must bear in mind the price of indifference every time we make a purchase.”10

End Notes:

1 These observations are based on Timmons Roberts, “Helping Tomorrow’s Climate Refugees by Engaging Today: A Dispatch from Bangladesh,” Brookings Institution, January 13, 2016.

2 “Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration,” The World Bank Group, March 19, 2018.

3 Roberts, “Helping Tomorrow’s Climate Refugees.” See also, K. M. Bahauddin, “Climate Change-induced Migration in Bangladesh: Realizing the Migration Process, Human Security and Sustainable Development,” Policy Brief for GSDR – 2016 Update.

4 John Vidal, “Remote Control,” The Guardian, March 26, 2008.

5 Vidal, “Remote Control.”

6 Mark Anner, “Binding Power: The Sourcing Squeeze, Workers’ Rights, and Building Safety in Bangladesh since Rana Plaza,” Penn State Center for Global Workers’ Rights (CGWR), March 22, 2018, p. 5.

7 Anner, “Binding Power,” p. 8.

8 Nikki Gilliland, “Four Factors Fueling the Growth of Fast Fashion Retailers,” Econsultancy.com, April 9, 2019.

9 Anner, “Binding Power,” p. 5.

10 Jason Motlagh, “A Year After Rana Plaza: What Hasn’t Changed Since the Bangladesh Factory Collapse," Pulitzer Center (the Washington Post), April 18, 2014.

Multimedia

Teacher Resources

Overview

We invite teachers to share ideas for using these materials in the classroom, especially how they can be used to build the curricular competencies that are prioritized in the new B.C. curriculum.

By registering with us, you will be able to access the for-teachers-only bulletin board. Registration will also allow us to send you notifications as new materials are added, and existing materials are updated and expanded.

For the sign in/register section:

Please register below to access the teachers’ bulletin board, and to receive updates on new materials.

Sign-in/Register

Registration Info

We want parts of this section to be secure and accessible to teachers only. If you’d like to access to all parts of the Teacher Resources, please sign-in or register now.

Sign-in/Register