“Womenomics” in Japan

Overview

Download as PDFWomenomics

Womenomics is a policy based on the idea that Japan can boost its economy by getting more women into the workforce, and they are rewarded with jobs and salaries that match their skills, talents, and ambitions. What are the challenges Japan is facing in getting more women working outside the home? And what changes is it trying to make to its economy, society, and culture to support more women working?

Will Women Help Solve Japan’s Economic Problems?

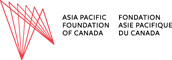

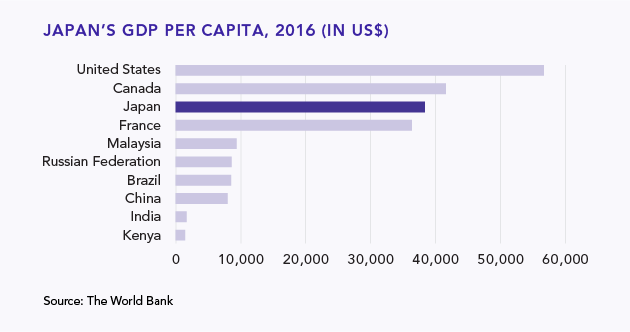

Japan is one of the richest countries in the world (see Figure 1), but its economy has people worried. After more than 20 years of slow growth (see Figure 2), it now faces a new challenge: not enough workers. In simple terms, this means that Japan’s companies will not be able to produce and sell as much as they would like – and the less they produce and sell, the less they will be contributing to Japan’s economic growth.

Figure 1: Japan's GDP per capita, 2016 (in US$).

Figure 1: Japan's GDP per capita, 2016 (in US$).

Figure 2: Japan's economic growth (GDP in US$).

Figure 2: Japan's economic growth (GDP in US$).

In 2013, the Japanese government rolled out a set of bold policies to try to kick-start the economy. One of these was “Womenomics,” women + economics. It is based on the idea that taking better advantage of the skills and talents of half its population – in this case, women – will help Japan solve its worker shortage problem. Compared to many other wealthy countries, fewer Japanese women work outside the home. Many who do have jobs, work part-time or for lower pay than Japanese men who do the same job. Why is Japan so short of workers? And what explains why the “gender employment gap” (the difference between men’s and women’s employment rates) has been so high in Japan?

Greying and Shrinking Population = Fewer Workers

One explanation for Japan’s current and future worker shortage is its population structure. Average life expectancy in Japan is long – 85 years. That means there is a relatively high proportion of people who are no longer working. In addition, Japan has a low birth rate. Most countries need a birth rate of about 2.1 births per woman to maintain the size of their population, but Japan’s birth rate is only 1.46.

In an effort to encourage more births, the government has tried to organize speed-dating events and other matchmaking initiatives, but, so far, these efforts have fallen short of expectations. As a result, Japan is adding fewer and fewer new people to its population – and to its workforce – every year. Between now and the year 2050, the country’s population is expected to fall from 127 million people to fewer than 100 million people. With a large older population that relies on pensions and high-priced health care and other services, Japan will need to do something quickly to find another source of tax-paying workers who can help support them.

Many wealthy countries like Canada make up for a low birth rate by opening their doors to immigrants, especially immigrants who are young and can do the type of work that is in high demand. Immigration to Japan has increased a little, including people from other Asian countries who can do “caregiver” jobs such as nannying, nursing, and caring for the elderly, and some manufacturing jobs. But Japan’s sense of nationhood puts a lot of emphasis on cultural homogeneity, and it has mostly resisted large-scale immigration as a solution to its “greying and shrinking” population. As of 2016, foreigners were still less than two per cent of Japan’s population.

That leaves Womenomics as Japan’s best option for filling the worker shortage. In 2013, the year the policy was launched, Japan’s labour force participation rate – the percentage of people within an economy who are either working or looking for work – was only 63 per cent for women, compared with 85 per cent for men. That 63 per cent includes women who are doing part-time or “irregular” (infrequent) jobs, but it does not include women who could be working but have given up on finding a good job. What explains this gap?

The (Partially Broken) Education-Employment Link

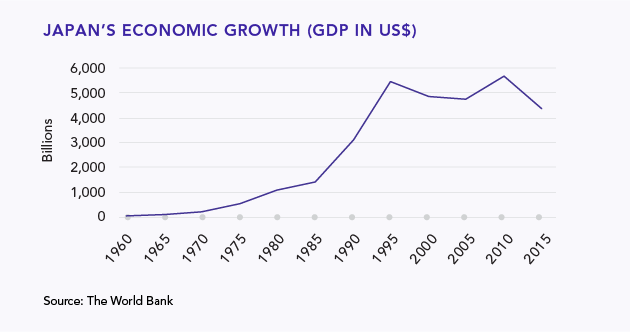

Many experts believe there is a strong link between education and employment. In other words, the more education a person has, the better her or his chances of getting a job. But this link is weaker for women in Japan than it is elsewhere. For example, the Global Gender Gap Report of 2016 measures four areas of gender equality – economics, politics, education, and health – in 144 countries (see Figure 3). On education, Japanese women rank extremely high, including ranking first in female literacy. But on “economic participation and opportunity,” Japan ranks 118th (see Figure 3). It is not simply that Japanese women and girls are highly educated compared with women and girls in other countries. By some measurements, they are also more educated than Japanese men; 59 per cent of Japanese women have a university degree, compared to 52 per cent of Japanese men.

Figure 3: Global gender gap, 2016.

Figure 3: Global gender gap, 2016.

With their higher rates of education, why do Japanese women have lower rates of employment and lower pay and status in the workforce? There are three main factors:

- Economic policies: In most Japanese families, the husband is the main income earner. If their wives work, the tax system allows husbands to take a “dependent exemption” (basically, letting them pay less in taxes) as long as the wife earns less than 1.03 million yen, or roughly C$12,000, per year. In response, says one analyst, “many women have lowered their working ambitions, taking low-earning, part-time jobs.” This is referred to as the “1.03 million yen wall,” or hyaku-san man en no kabe.

- Social welfare policies: In many countries, it is common for women to leave the workforce temporarily after they have a child. But in Japan, 70 per cent of them leave and do not return for at least 10 years, if at all (compared to 30 per cent in the United States). One reason is the lack of available childcare, not just for infants and toddlers, but also after-school care for primary school students. This is another kind of “wall,” called the “first grade wall,” or sho-ichi no kabe.

- Cultural and social norms: According to one group of Japanese analysts, “one of the greatest barriers to higher Japanese female employment is Japanese society itself.” This takes many forms. For example, in Japan, getting a promotion at work is often based at least partly on tenure, which refers to the length of time a person has worked for a company or other organization. This has disadvantages for those women who leave their jobs temporarily to have children. Japanese work culture also tends to reward people for their willingness to work overtime, and for going out with one’s supervisor and co-workers after work for team-building purposes. This sometimes includes late nights of drinking with co-workers, which is seen as an extension of work. In a country where women still have the primary responsibility for being at home to care for children, it is far more difficult for them to do overtime or participate in these after-hours activities.

Some Japanese women say that, because of this type of work culture, they experience workplace bullying. “Maternity harassment,” or matahara, might happen when a woman becomes pregnant or gives birth and needs to take leave or work shorter hours. Some experience sekuhara, sexual harassment, or powahara, power harassment, which happens when people with power do things like humiliate co-workers who have less power.

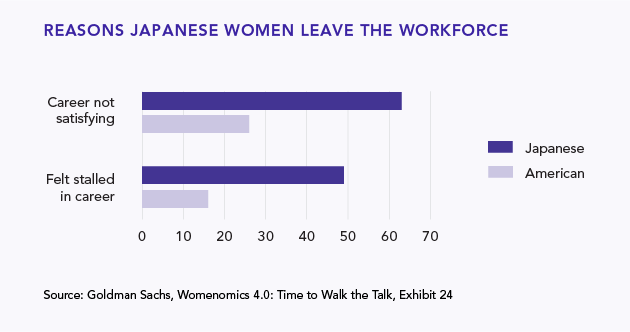

Another factor discouraging women from working is the difficulty they face in getting jobs or promotions that match their ambitions, talents, and hard work (see Figure 4). This is by no means unique to Japan. However, it has been observed that, within a company or organization, Japanese men are often put on a track that gives them more responsibility, more opportunities for leadership, and higher pay. Meanwhile, women with similar skills and work ethics might be put on a different track with less challenging work and fewer rewards. Because of this, it is especially difficult for Japanese women to reach top positions within businesses or the government.

Figure 4: Reasons Japanese women leave the workforce.

Figure 4: Reasons Japanese women leave the workforce.

Finally, there is a sizable minority of young women in Japan who prefer to be housewives rather than working in full-time careers. One survey from 2013 showed that one-third of Japanese women between the ages of 15 and 39 said they wanted to get married and become a full-time housewife. It should be noted that being a housewife is respected in Japan, more than in some other countries.

Is Womenomics Closing Japan’s Gender Gap?

The results of the Womenomics policy so far have been mixed. On the plus side, more Japanese women are entering the workforce – now up to 66 per cent – and there are more daycare spots available to support mothers. And the “1.03 million yen wall” is expected to be raised to 1.5 million yen.

In addition, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (pronounced AH-bay) committed to appointing women to top cabinet positions. Unfortunately, some of these women had to resign due to scandals, which could be a setback for efforts to encourage more people in Japanese society to see men and women as having equal abilities. But Tokyo, a mega city whose population is roughly the same size as that of Canada, elected its first female governor in 2016. She is one of the country’s most popular politicians, and some think she could become Japan’s first female prime minister. She is now the country’s most popular political leader, and some think (and hope) she can become Japan’s first female prime minister.

There are reasons to be optimistic that the work culture in Japan is also becoming more female-friendly. For example, newer companies with younger employees seem to be more open to change than older companies with older employees. Also, says one expert, even the male-oriented norm of working overtime is starting to change: “The macho thing in work culture is under pressure,” she says. “It used to be cool to work to midnight, now it is very uncool.”

But some women are frustrated with what they see as the slow pace of change. They point out that it will take bold leadership to change the “ingrained sexism” that holds so many of the country’s women back. What may ultimately make the difference in giving Japanese women the same opportunities and support as Japanese men is the economic urgency that impacts all Japanese people. “While gender inequality is increasingly understood to be a human rights issue,” says one report, “for the Japanese government, it remains above all an economic issue.”

Multimedia

In the News

- WOMENOMICS

Teacher Resources

Overview

We invite teachers to share ideas for using these materials in the classroom, especially how they can be used to build the curricular competencies that are prioritized in the new B.C. curriculum.

By registering with us, you will be able to access the for-teachers-only bulletin board. Registration will also allow us to send you notifications as new materials are added, and existing materials are updated and expanded.

For the sign in/register section:

Please register below to access the teachers’ bulletin board, and to receive updates on new materials.

Sign-in/Register

Registration Info

We want parts of this section to be secure and accessible to teachers only. If you’d like to access to all parts of the Teacher Resources, please sign-in or register now.

Sign-in/Register