Chinese Migrations in the Mid-Late 19th Century

Overview

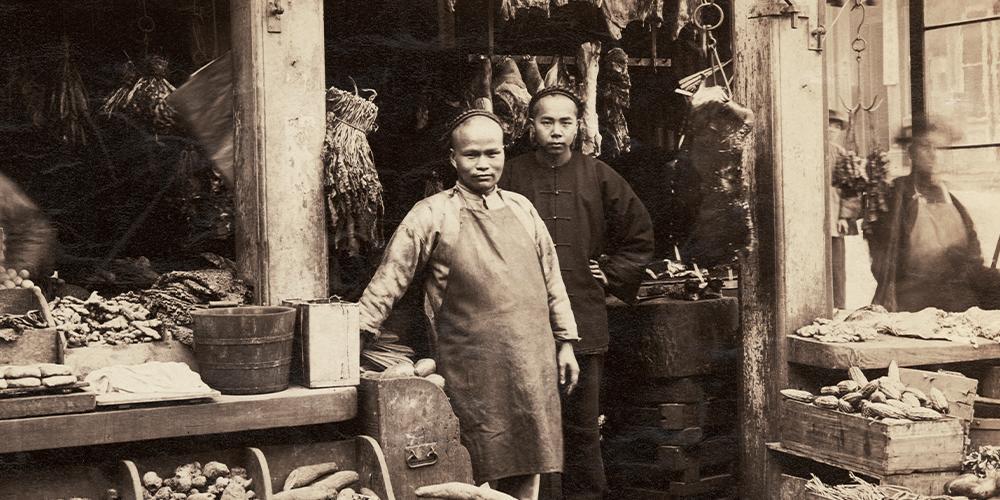

Download as PDFIn China, there is an old saying that “a thousand days at home are good; a day away from home is hard.”1 The saying was attributed to Confucius, whose philosophy emphasized the importance of family and respecting one’s elders. That meant staying close to home. For centuries, people in China tried to heed that advice. But starting in the mid-19th century, millions of Chinese pulled up stakes and left for unfamiliar and faraway places, both within and beyond China’s borders. Why and how did this happen?

This introduction to Chinese migration looks at some of the factors that caused so many people to move – economic, demographic, technological, social, political, and other factors. Some factors played a direct role; others played an indirect, but still very important, role. It also looks at different types of migration and the consequences for those who migrated, those who were left behind, and the places that became their new homes away from home.

Confucius was correct that being away from home is hard. Yet migration was a path that millions of Chinese people took in the mid-19th century. By examining the causes and consequences of this migration, we can better understand the major events and changes happening during this period, both in China and in the wider world. It also helps us think about similarities and differences with migration in other countries and at other periods of time, including today.

The Context for Migration: China’s Tumultuous 19th Century

The wave of Chinese migration starting in the 19th century happened in the final century of the Qing Dynasty. The Qing, who were in power from 1644 to 1911, began their reign as effective rulers. They brought about a long period of peace, expanded the size of the empire, and raised the standard of living for millions of people. But by the mid-1800s, they were struggling to respond to mounting challenges from within China and from international actors and forces. Some of the biggest factors that shaped the 19th century – and the context for migration – are described below.

Factors Within China

Expanding the empire: The Qing more than doubled the territory under their control (see Map 1). Many of the newly incorporated areas in the north and west were sparsely populated, but they added ethnic and religious diversity to the country. This included Mongolians, Tibetans, Muslim populations, and others. Even the Qing were not from the Han ethnic majority. Rather, they were Manchus from Manchuria, north of the Great Wall.

Map 1: Chinese Territory during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

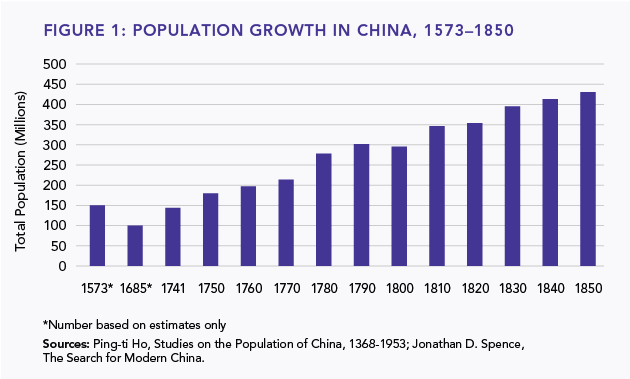

Population growth: Qing government officials introduced new irrigation and water management techniques. These techniques helped to limit the damage from floods and droughts and increased China’s food supply. So too did the introduction of new strains of rice in the south, and crops from the Americas, such as peanuts, corn, and sweet potatoes. These imported crops could be grown in areas of China where it was otherwise difficult to grow food, and that allowed new lands to be opened up and settled in the southwest and northeast.

As nutrition improved, China’s population grew rapidly. In the early 1600s, the population had decreased because of the violence and chaos that accompanied the previous dynasty’s collapse. But by the 1740s, it rebounded to about 140 million. By the end of the 18th century, the population doubled to nearly 300 million. By 1850, it had climbed to 430 million (see Figure 1).

Population growth can benefit a society, especially if it leads to increased economic activity. In late imperial China, it also created social and economic strains. China had not yet adopted industrial manufacturing on a large scale, and most people supported themselves through farming. Farmers who owned their land followed a tradition of dividing up the land equally among the family’s sons. But the amount of farmland did not expand enough to absorb the growing population, even with the opening of new lands. Therefore, in some parts of the country, people struggled to support themselves on smaller and smaller plots of land. Many other farmers rented their land from landowners, through a system called tenant farming. These farmers were squeezed from two sides: they had to pay rent to their landlords, usually as a portion of what they produced, and they also had to pay taxes to the government.

Figure 1: Population Growth in China, 1573-1850.

Declining governance: The size of the bureaucracy in the late Qing period did not expand at the same rate as population growth. With more people to govern, Qing officials were stretched thin and could not do their jobs effectively. In fact, many of them neglected their responsibilities and focused instead on enriching themselves by engaging in corruption – for example, collecting taxes from farmers, but not providing the services that improved the farmers’ lives. Even members of the military and those who were responsible for water management were becoming less effective or ineffective, and often more corrupt.

Lack of employment opportunities: Although the bureaucracy’s reputation had gotten worse, many educated young men still aimed to get a government job. The reason was that few other types of employment provided the same social and economic benefits and status. These young men were under tremendous pressure because their families sacrificed a lot to pay for the education that prepared them for the imperial exam. If he passed the exam and got a government position, it would raise the whole family’s status. But as the population grew, more young men were competing for – but failing to get – these government positions.

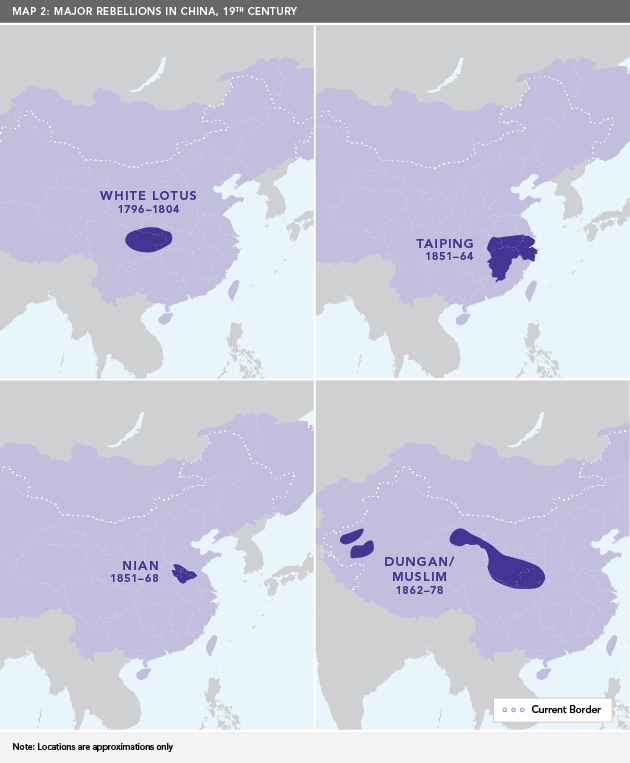

Internal upheaval: Throughout the 19th century, there were several large-scale rebellions and peasant uprisings throughout China. These were based on a variety of grievances, including poverty, famine, anger at official corruption, and a strong dislike of the Qing. Some were also inspired by new religious ideas or ethnic identities. All of the rebellions were eventually defeated, but they took a heavy toll on the Qing, and an even heavier toll on the people and areas that were directly affected (see Map 2).

Map 2: Major Rebellions in China, 19th Century.

Factors from Outside China

Foreign intrusion: In the 1800s, foreign powers were becoming more aggressive in their efforts to access China’s resources and large market. The first major confrontation was the Opium War against Great Britain (1839-1842). The British were demanding the right to sell opium to Chinese consumers. The Qing state, fearing the social consequences of opium addiction, tried to defend itself against Britain’s demands. But once the two sides went to war, the Chinese were no match for the technological superiority of the British navy.

As a result of their defeat, the Qing had to allow the sale of opium. It had exactly the kind of impact they feared. They also had to pay a huge indemnity to the British for damage and losses during the war. In addition, China was forced to open several treaty ports to foreign presence – not only foreign governments, but also foreign business interests. The new treaty arrangements also forced the Qing to end their ban on Christianity. It had been banned because Christianity was seen as a challenge to China’s Confucian belief system. Once the ban was lifted, the number of Christian missionaries from Europe and the United States grew, and they expanded their efforts to convert Chinese souls.

Image 1: Opium War.

Foreign intrusion in China did not end there. In 1860, China lost a second Opium War against Britain and France, while at the same time it worried about Imperial Russia’s expansion into the Far East, just north of China. Toward the end of the century, China suffered perhaps its most shocking and humiliating defeat of this period: a loss to Japan, a country it always considered inferior, in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). Japan’s victory gave it control over the island of Taiwan, off China’s southeast coast, and a foothold in the resource-rich Qing heartland of Manchuria.

New transportation technologies: New forms of transportation that arose out of the Industrial Revolution in Europe were making their way to China and other parts of the world. This included steamships, which made sea crossings safer and faster. It also included railroads. Like steamships, railroads were an efficient way to move raw materials, finished goods, and people across land. But they also had another important effect on China. The construction of railroads required a lot of workers to do the difficult and often dangerous work of clearing land and laying tracks. Railroad construction projects in China and other countries began looking for people to fill these jobs (see “Growing demand for labour,” below).

Growing demand for labour: Current and former European colonies in the Americas, Southeast Asia, Australia, and other far-flung places needed workers for agriculture, construction projects, and extracting natural resources. This included plantations – rice, rubber, fruit, sugar, and tea plantations, for example – and the dreadful work of mining guano – dried and baked bird droppings used in fertilizer and gun powder. Foreign companies went in search of a new pool of cheap – and exploitable – workers. They set their sights on China because of its large labour force and the opportunity created by the opening of treaty ports.

Questions About Connections to Migration

Many factors made the 19th century a time of great change and upheaval in China. Thinking about how these factors related to migration raises several questions:

- What forms did migration take?

- Which factors mattered the most? Did these factors work alone, or in combination with others?

- Did the factors play a direct role or indirect role?

- What was the role of the Qing government, and did it change across cases or over time?

The next sections introduce two main types of 19th-century Chinese migration: flight migration and economic migration (internal and international). They also provide case studies for exploring these types of migration in more detail.

Types of Migration

In the mid-to-late 19th century, there were two main types of Chinese migration:

- Flight migration, driven by the need to escape unsafe conditions, such as war, disease, natural disasters, poor governance, or persecution because of one’s race, religion, or political beliefs; and

- Economic migration, driven by the need or desire to improve one’s economic situation by moving elsewhere for a business or job opportunity.

Both types of migration can be temporary or permanent, and both can be internal (within a country) or international.

Economic migration during this period had three important features.

- It followed a pattern of chain migration, in which the earliest migrants to a location returned to their villages or nearby areas (often sent by their bosses) to recruit more workers.

- Most economic migrants were men, especially young men. The view at the time was that women were not suitable for the types of jobs that migrants did – agriculture, construction, and mining. However, limiting migration mostly to men made many overseas Chinese communities unsustainable. Often, migrants left behind wives and families, or wanted to return to their hometowns as soon as possible to get married and have children, thus fulfilling their Confucian duty to carry on the family line.

- Migration was often a family decision made based on how it could help the migrant’s family, which remained in China. For example, if a new economic migrant received a recruitment bonus, the money was often given to or shared with his wife or parents. Once the migrant began receiving payment for his work, he was expected to save as much as possible to send home. These payments were called remittances. If a migrant’s family was heavily dependent on the remittances, he carried a heavy burden of having to work hard, live cheaply, and sometimes endure terrible circumstances.

The case studies that follow explore in more depth three examples of 19th century Chinese migration: flight migration, internal economic migration, and international economic migration.

Note: The PDF available on this page includes launch activities, lesson challenges, briefing sheets that introduce two main types of 19th-century Chinese migration: flight migration and economic migration (internal and international). They also provide case studies for exploring these types of migration in more detail.

About the Author

Jack Patrick Hayes, PhD, is a professor of Chinese and Japanese history at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Vancouver. His research focuses on late imperial and modern Chinese and Tibetan environmental history, resource development, and ethnic relations in western China.

End Notes:

1 Zajia qianri hao chumen yichao nan. Confucius. 5th century. The Analects.

Teacher Resources

Overview

We invite teachers to share ideas for using these materials in the classroom, especially how they can be used to build the curricular competencies that are prioritized in the new B.C. curriculum.

By registering with us, you will be able to access the for-teachers-only bulletin board. Registration will also allow us to send you notifications as new materials are added, and existing materials are updated and expanded.

For the sign in/register section:

Please register below to access the teachers’ bulletin board, and to receive updates on new materials.

Sign-in/Register

Registration Info

We want parts of this section to be secure and accessible to teachers only. If you’d like to access to all parts of the Teacher Resources, please sign-in or register now.

Sign-in/Register